I spent two days reading Redux in Action.

Combining the book with more than a year of React/Redux experience, I jotted down reflections—mostly small but important details to watch in real projects.

State Is Read-Only

We should not mutate state directly inside reducers (or sagas/effects). Technically we can, but we shouldn’t. Mutating the original state doesn’t throw errors, yet React won’t re-render the components.

A counterexample:

case 'UPDATE_USER_AGE':

state.age += 1;

return state;

Dispatch this action and inspect the state with Redux DevTools: the number increases, but the React component never updates because no re-render occurs.

The state changed, but React didn’t notice. Why? Because of connect.

connect Checks References

const mapStateToProps = function (state) {

return {

user: state.user

};

};

Redux uses a shallow equality check. If the user reference doesn’t change, mapStateToProps keeps returning the same object, so React thinks nothing changed.

Conclusion: never mutate state directly, or you invite bugs.

Sync vs. Async

In React-Redux + redux-thunk + redux-saga setups—or plain JavaScript—the sync/async story is unavoidable. Within Redux:

- Dispatching an action from the view to the store is synchronous, and components synchronously subscribe to store changes. However, React still has to run through lifecycle updates, so dispatching an action and immediately reading state from props doesn’t guarantee you see the latest values. Remember,

connectultimately callssetState, andsetStateis async. - Inside redux-saga effects, dispatching an action and then calling

selectto read state does yield the latest value. As above, the pipeline is synchronous. - redux-thunk lets actions return functions (even Promises). When you dispatch a function, you’re embracing asynchronous control flow.

Action Payload Naming

Example action creator:

export const setBooksInfo = (books) => ({

type: 'BOOKS_FETCH_SUCCEEDED',

books

});

A better practice is to wrap parameters inside payload. Two benefits:

- You avoid naming collisions with the reserved

typefield. If you ever need a field literally namedtype, you can still place it underpayload. - If you spread the action (excluding

type),...actionwould otherwise pull intype. With payload, you can safely destructure all custom fields.

That’s why Flux Standard Actions (FSA) recommend payload.

export const setBooksInfo = (books) => ({

type: 'BOOKS_FETCH_SUCCEEDED',

payload: { books }

});

More details: https://github.com/acdlite/flux-standard-action

Container vs. Presentational Components

Redux popularized splitting components into containers and presentational pieces, often mirrored in a containers/ + components/ folder structure. Technically it separates Redux-aware components from pure UI.

Personally I don’t love the pattern. React is ultimately an interaction library; every component serves the UI. I prefer organizing components by feature/usage and extracting shared pieces into shared/. Whether a component connects to Redux should be guided by team conventions and code reviews, not directory hierarchy.

Remember: Redux and React are just libraries. They don’t mandate folder structures. Adopt what works for your team.

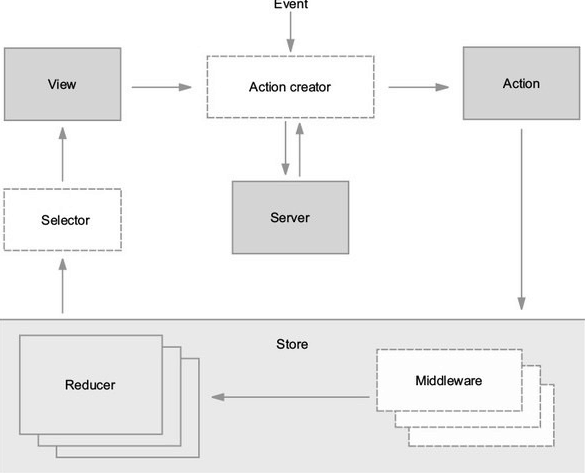

Redux Middleware Flow

action dispatch → middleware chain (e.g., middleware1, middleware2) → reducers update the store → connected components receive updates and re-render.

When to Use Redux-Saga vs. Redux-Thunk

- Use sagas for complex, long-running processes.

- Sagas and thunks can coexist; Redux accepts multiple middlewares.

- Both handle side effects. Anything a thunk can do, a saga can also do. For simple effects (e.g., a single network request), thunk is fine. For multi-step flows, sagas keep the code cleaner.

Performance Tips

React and Redux are lightweight, but it’s still easy to waste cycles. A few points:

- Map only the slices of state a component actually needs. Redux state is a single tree, but subscribing to the entire root is overkill. You either never re-render (if references stay equal) or over-render unnecessarily.

- Choose between

React.ComponentandReact.PureComponentwisely.Component’sshouldComponentUpdatealways returns true.PureComponentshallowly compares props and state:

if (ctor.prototype && ctor.prototype.isPureReactComponent) {

return (

!shallowEqual(oldProps, newProps) ||

!shallowEqual(oldState, newState)

);

}

shallowEqual in turn checks keys and shallow value equality.

function shallowEqual(objA, objB) {

if (is(objA, objB)) return true;

if (typeof objA !== 'object' || objA === null ||

typeof objB !== 'object' || objB === null) {

return false;

}

const keysA = Object.keys(objA);

const keysB = Object.keys(objB);

if (keysA.length !== keysB.length) return false;

for (let i = 0; i < keysA.length; i++) {

if (!hasOwn.call(objB, keysA[i]) ||

!is(objA[keysA[i]], objB[keysA[i]])) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

PureComponent adds this shallow comparison step during shouldComponentUpdate. If you extend React.PureComponent, don’t reimplement shouldComponentUpdate yourself.

Example

export class NumberList extends React.PureComponent {

render() {

console.log('render list');

const listItems = this.props.numbers.map((number) => (

<li key={number.toString()}>{number}</li>

));

return <ul>{listItems}</ul>;

}

}

If the parent re-renders but the numbers reference doesn’t change, NumberList doesn’t re-render (no console output). Switch to React.Component, and every parent render re-runs the child render method. React’s diffing prevents DOM churn, but calling render still has a cost—avoid it when possible.

When to Use PureComponent

Use PureComponent when props and state are immutable. Otherwise fall back to Component. In the example above, the parent passes an immutable numbers array, so PureComponent fits.

Final Thoughts

Just a handful of notes—call it a mini book report.