window.openerisn’t new, but it’s easy to overlook. Here’s why it matters.

What does window.opener do?

The Window interface’s

openerproperty returns a reference to the window that opened the window, either withopen(), or by navigating a link with atargetattribute.

In short, opener lets one window operate on another—within limits.

Example: Page A opens page B. You want B to trigger a refresh in A when a button is clicked. opener can help.

When does opener exist?

Sometimes window.opener is null. Conditions:

- Same-site

- Same-site is looser than same-origin: only protocol and eTLD+1 must match.

- A linking relationship exists

- A opens B via an anchor,

window.open, or within an iframe. - If the user types B directly in the address bar, A and B have no relationship.

- A opens B via an anchor,

If conditions are met, A opens B and B can access window.opener. They also share the same renderer process.

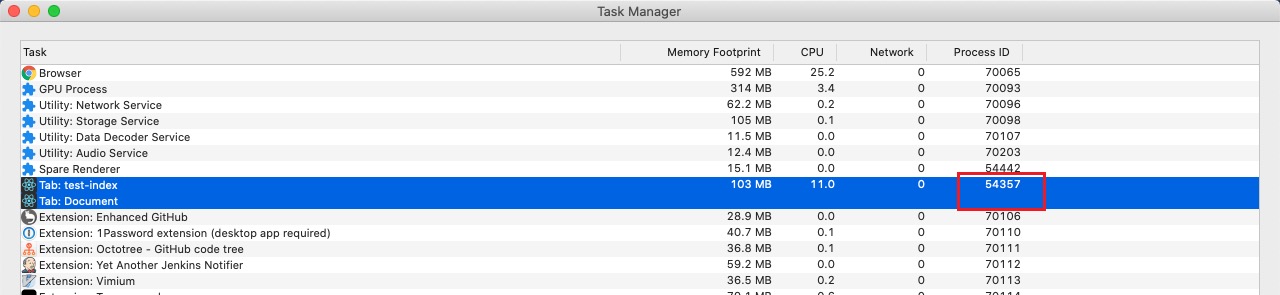

Chrome has a UI to inspect processes: three-dots menu → More tools → Task Manager.

In this screenshot, two same-site tabs share a process:

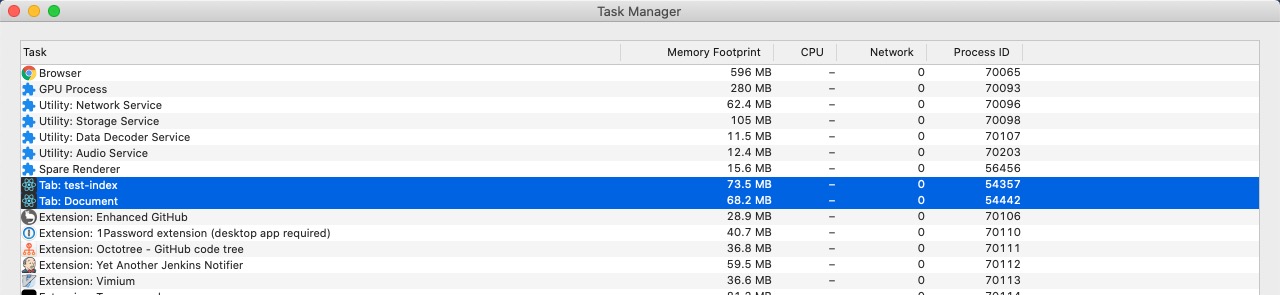

Slight changes to page code may result in separate processes:

noopener

Sometimes A opens B and they’re same-site, yet separate processes. Why? Special settings.

Both window.open and <a> support noopener (via rel="noopener" for anchors). With noopener, B opens in a new renderer process and cannot access window.opener.

Notes

- In Chrome, if you don’t explicitly set

rel='opener'on an<a>, the browser may open a new process. - With

openerenabled in a same-site context,sessionStorageis shared. Usenoopenerto avoid this.

eslint

For performance and safety, new tabs often prefer noopener. Enforce it with lint rules:

'react/jsx-no-target-blank': ['error']

Pros and cons of sharing a renderer process

Pro: shared resources, lower overhead. Con: if tab A crashes, tab B may crash, too. Make a trade-off.